The country’s first female-run radio station was looted and its staff persecuted but, despite the risks, women in the media are making their voices heard

When Radio Shaista goes silent, you know the Taliban are close. The female-run radio station was looted and wrecked when the group captured Kunduz, Afghanistan’s embattled northern city, in 2015, sending journalists fleeing. Even after the Taliban were routed, female journalists have been on guard, if they ever returned, that is.

Zarghoona Hassan, Radio Shaista’s director, fled after armed militants knocked on her door at home. They accused her of converting listeners to Christianity and announced a date for her execution.

She says the Taliban’s anger was fuelled by talk of empowering women. The radio broadcast discussions with religious scholars about women’s rights and called on mothers of Taliban combatants to prevent their sons from fighting.

“We had conversations about women studying, and talked about female pilots,” says Hassan.

Hassan now splits her time between Kunduz and the capital, Kabul. Since 2015 she has shut down her radio station twice in fear of Taliban advances.

A vibrant media is one of the great successes of post-2001 Afghanistan. However, women’s position in it is fragile. For many Afghan families, when security worsens, protection of women overrides most other concerns.

“[When we started], women flocked to the radio to work, even for free. But when the Taliban came closer, around 2012, people’s attitude changed,” says Hassan, who founded two other radio stations in Kunduz. “Many women in Kunduz want to work in media but their families won’t let them.”

This anxiety highlights the complexities around western endeavours to empower Afghan women, particularly outside liberal, urban classes. And when efforts to promote human rights do make Afghan women visible, they are usually cast as victims.

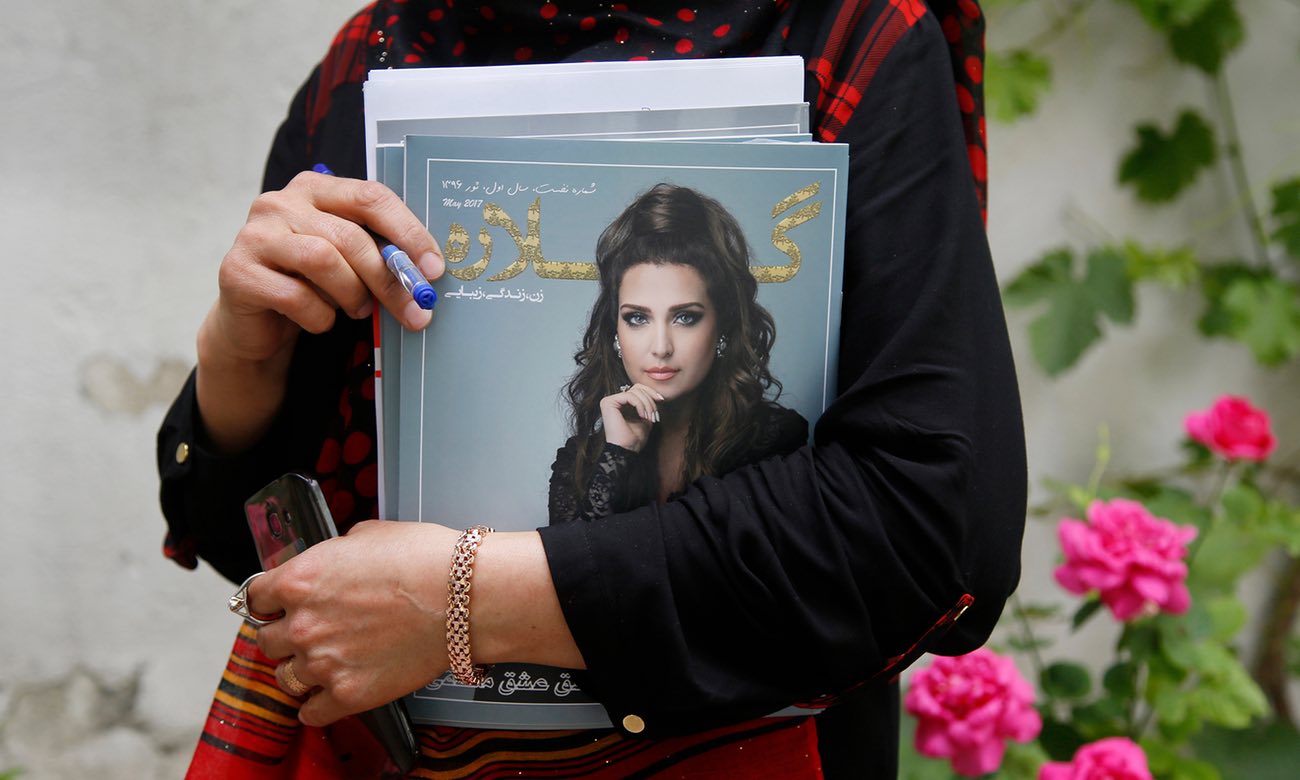

One magazine is hoping to change that. In May, the first issue of Gellara, Afghanistan’s first women’s lifestyle magazine, hit the newsstands.

“Until now, the media mostly focused on women facing violence, baad [compensating for a crime by giving a woman away in marriage], and women who had their faces cut,” says Fatana Hassanzada, 23, the magazine’s founder and editor. “We want to portray other faces of women.”

Modelled on international magazines like Vogue, Gellara addresses Afghan women as consumers of fashion and culture, as book readers and as love seekers. “As human beings,” says Hassanzada.

The cover of the first monthly issue, 2,000 copies of which were printed at offices in Kabul, features Canadian-Afghan singer Mozhdah Jamalzadah, her hair unveiled. Inside, articles on breast cancer and yoga follow pieces on Iranian film and beauty.

“We want to show that a woman can have a pretty face and be well dressed. We are trying to teach society not to be shocked by these things,” says content editor Aziza Karimi.

Perhaps most controversial, in a country where arranged marriages are still widely enforced, is an introduction to the dating app Tinder.

When asked how that would go down in conservative rural areas, Hassanzada laughs. “We try to target everyone. There is something for the cities and something for the villages,” she says, while recognising that many rural women would probably only see the magazine if their husbands brought it home.

This month, Afghanistan also saw the launch of Zan TV (Women’s TV), the first channel dedicated to women. Female presenters are common on Afghan television, but Zan is the first with all-female newsreaders (though its owner is a man).

Mehria Afzali, 25, a presenter, says her parents opposed her working in media until her husband convinced them. “Some people in the provinces believe women on TV are destroying the unity of the family,” she says. “But we wear proper hijab. We are an Islamic channel.”

Conditions for Afghan journalists are deteriorating. Last year was the bloodiest for media workers since 2001, according to the Afghan Journalists Safety Committee.

Though cities offer a larger, liberal audience, they are not always safe. A few years ago, Hassanzada, then a TV presenter, fled to Kabul from Mazar-i-Sharif with her family after a group of men stabbed her younger brother in the street, demanding that she stop working.

In Kabul, she faces threats, too. On a visit to Kabul University this week to promote the magazine, students from the Islamic law faculty tried to intervene, calling the magazine “infidel”, before security blocked them.

Hassanzada says she would not go back to the university. “But three of our reporters study there. I am worried something will happen to them.”

Yet, she says, reporting on controversial topics is worth the risk. “We are the second generation of democracy in Afghanistan. In a revolution, there will always be sacrifices.

“These issues are not dangerous. It’s society that’s dangerous.”

Source: The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2017/may/31/female-journalists-defy-taboos-braving-death-threats-afghanistan

0